FEATURED POSTS

-

November 9, 2016

Coming to Terms with the Past

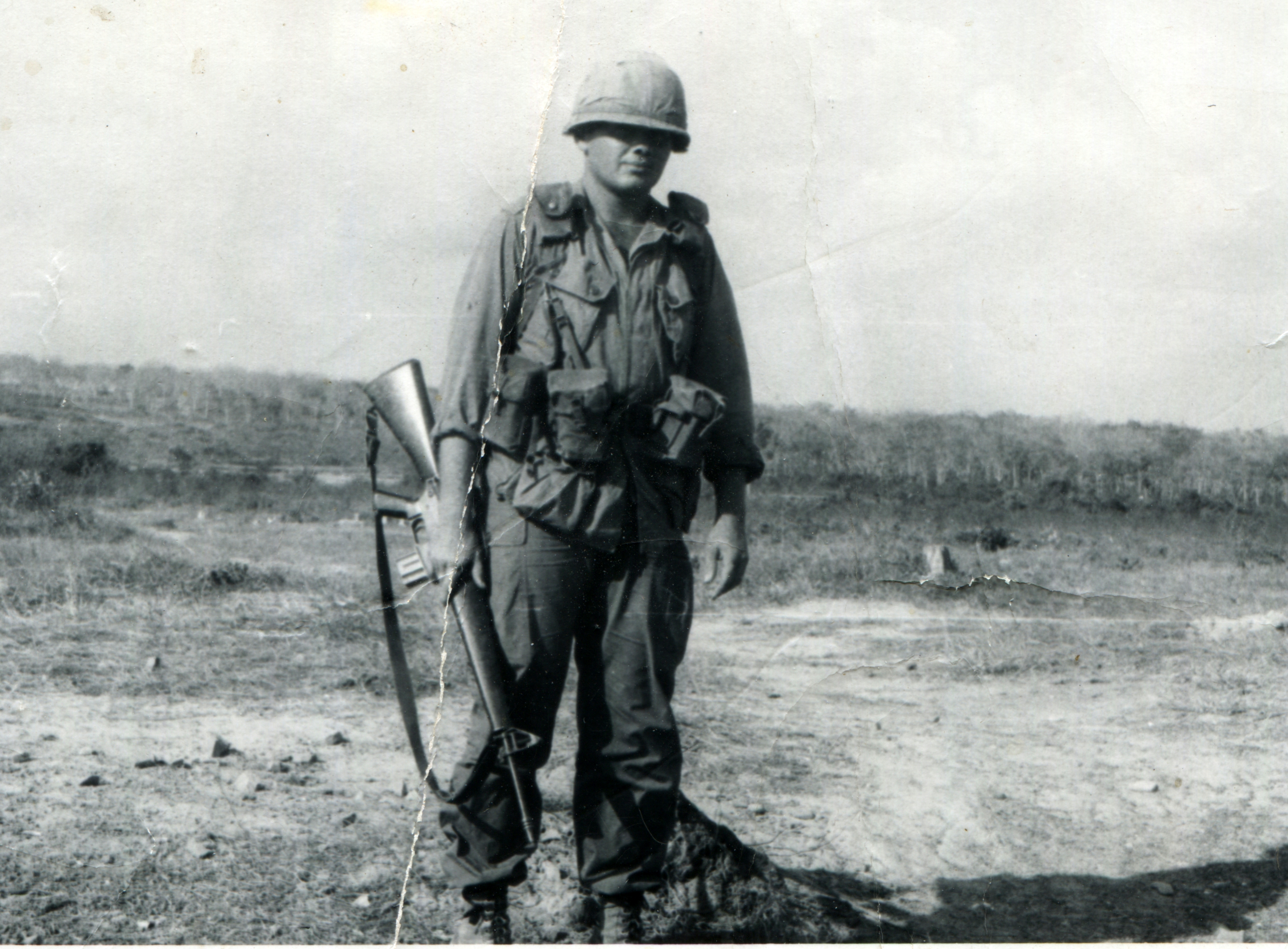

Fifty-one years ago today, my life changed forever. There have been many changes since that time, some extremely good and some not so much, but I was one person before November 8, 1965 and another person afterwards.

I don’t like to talk about it. I have tossed and turned through many sleepless nights, trying not to think about it, but now, more than half-a-century after that day, maybe it’s time to write about some of my unresolved issues. For perspective, you can go on the internet and google “November 8, 1965, Vietnam.”

It wasn’t the bloodshed or the horror of war. By November 1965, I had seen quite enough of that. But the date marked the biggest Vietnam battle involving U.S. troops up to that time, although bigger and bloodier battles would come as the conflict dragged on. And I was medevacked early in the fight, so I was gone well before the worst of it.

The thing is, I knew it was going to happen days before it did. But, I got it wrong. I was certain – positive – that I was going to die on the next mission. I even thought about writing a good-bye letter home, but what would I say?

“Dear Mom.

I’m going to die in the next few days, please take care of my little brothers.

Love George.”

And so I didn’t write the letter, which was a good thing because I didn’t die.

The platoon sergeant who was standing near me was killed, my radio operator who was standing next to me was killed, and the medic who was standing between me and the mortar round that exploded in our midst was killed. His body shielded me from much of the flying shrapnel. In fact, I was the last life he ever saved.

I’ll skip the gory details, except to note that when Gen. Willian Tecumseh Sherman said “War is Hell” in 1870, he was not exaggerating.

I also will not reveal the names of my comrades who died that day, except to say that the platoon sergeant, who bled out on the floor of the helicopter during my ride back to a tent hospital, was a 34-year-old black man with a big smile and a kindness that belied his choice in careers.

The medic was a sweet-natured 19-year-old white kid, who dreamed of turning his Army job saving lives into a civilian pursuit after he was discharged.

My radio operator and I were from the weapons platoon. I was a forward observer, whose job was to call in mortar fire when the need arose. In the jungle, you usually couldn’t see far enough through the underbrush to call in fire. During those times, I basically became just another guy with a gun. On November 8, 1965, I was three weeks shy of my 25th birthday.

To be honest, I was not particularly pleased with my radio operator. He was 18-years-old, fresh out of some inner-city slum, with a bad attitude and a chip on his shoulder. He had been shot in the butt 34 days earlier, and the forward observer to whom he had been attached was killed. It was just a flesh wound, and it healed quickly, but it shook him to his core.

The sad truth was that he was a kid, and he was scared. He had the same premonition that I did – a premonition that he was going to die on the next mission. He had literally begged the weapons platoon sergeant not to make him go, but you don’t get off the hook because you’re scared. Everybody was scared. I was not particularly happy when he was assigned to me, but he got way worse than he deserved.

I mention race, only to note that it didn’t seem to matter a whole lot on the battlefield. We were infantry. Our battalion was just about equally divided between black guys and white guys with a few Hispanics and other minorities mixed in. We didn’t choose our friends by race. It wasn’t exactly a warm and fuzzy love fest, but you knew who you could count on and trust and who you could not, and it had little to do with the color of anybody’s skin.

When they finally got a helicopter to land in the middle of bullets flying through the trees, they loaded it so full, I had only a few inches of seat with my knees hanging out through the open doorway. Despite the noise of the engine and rotor, I remember the flight back as a quiet time. A couple of thousand feet above the jungle canopy with the doors open, the slip stream rushing past, it seemed cool and unreal as I went into shock. I am not religious – not then and not now – but I remember singing to myself all the hymns I learned going to the Baptist Church with my grandmother when I was barely 5.

The Old Rugged Cross, Bringing in the Sheaves, Peace in the Valley. And all the time I was wondering, why am I still here? Why am I alive when the others standing next to me are dead?

It would be nice to say that I saw the experience as a second chance, that I took control of the rest of my life and did something grand and good with it. Maybe I should have, but I did not. My experience was no more terrible or unique than thousands of other young men who fought in that mindless war and the terrible wars that followed.

Fifty-one years later, I’m doing pretty well. I have a woman who loves me, a couple of bucks in the bank, and a place to get out of the cold. I’m actually happy – maybe happier than I have ever been.

But the ghosts still come around on those sleepless nights, to stand sad and silent by my bed. Why you, they want to know. How come we died so young and you lived to be so old.

I have no answer, but I do think about them still. Especially on this day, 51 years later.

— George Cunningham

— george@georgeleecunningham.com