Featured Posts

Do the dead hold grudges?

I hope not. I hope that after folks have passed on, all the grievances and the differences that separated them in life are buried along with the physical bodies they no longer need.

But it’s hard to say, especially in a small town like Ely, Nevada, where friends and enemies in life end up just a few feet from one another, buried beneath the gravely surface, in coffins separated only by dirt and the roots of tall trees. Some of the dead have fancy stones above their graves, others have more simple plaques, but financial or social status doesn’t mean that much when you’re dead.

The Ely City Cemetery is small – unlike the Forest Lawn or Rose Hills or Arlington mega-cemeteries of Southern California. The graves come down almost to the sidewalk along busy E. Aultman Street, separated only by a 30-inch rock wall. Across the street is the Big 8 Tire Store and the Cruise-In Car Wash and Mini Lube.

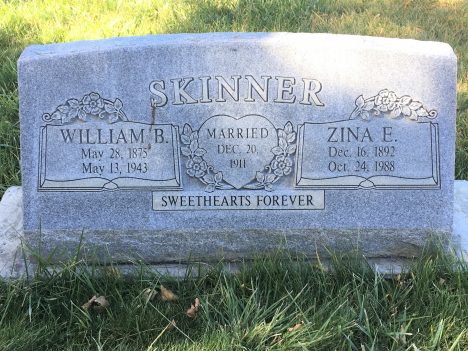

Most of the graves at the Ely cemetery are actual upright stones – not the little flat plaques in the ground that make it easier to mow the grass and keep down maintenance costs, as is common in newer big-city plots. The upright stones makes it quicker to locate the graves of loved ones and gives each grave a little personal style of the person or persons buried beneath.

Except for the sound of nearby traffic, the Ely cemetery is blissfully calm on a weekday morning. Aultman is a busy street in Ely with a fair amount of traffic. People driving home from work or going out to eat drive right past the final resting place of family and friends. You wonder how many driving past at 40 mph give a sad nod to loved ones who are departed. And how many folks getting a new set of tires at the Big 8 ever wander across the road for a quick visit with the memories of those long gone. You see fresh flowers on some of the graves, sometimes of people who have been dead for 10, 20 years and more – colorful remembrances of lost relationships.

Ely was a mining town, populated with people from all over the world – Asians, Italians, Slavs, French Basques, English, Greeks, and Native Americans. It was a small town reflection of American society at large, a melting pot of cultures, cuisines, and religions. It is a mix well-represented at the cemetery.

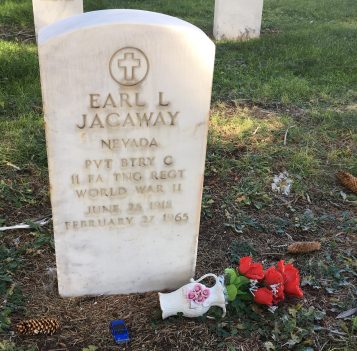

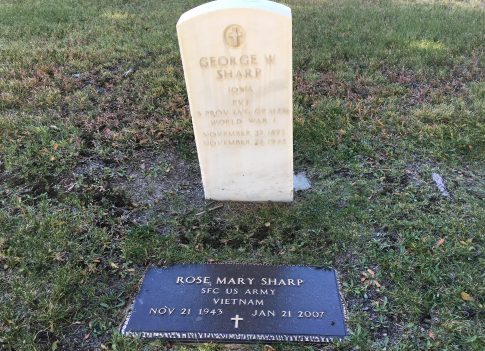

In a shady grove, set off to one side, is the section for Ely veterans, who served their country. You find the graves of veterans lined up in rank and file from World War I, World War II, Korea, Vietnam, and the newer ones from the current era. Ely’s recognition of those who served.

Some of them have their wives buried next to them, joined in death as they were in life. There is even a father and a daughter – him a private from World War II, she a sergeant first class from the Vietnam War.

The Ely graveyard, like all graveyards, contains both mysteries and secrets. Who were the people interred beneath the sod. How did they die, and are their graves near their friends or beside their bitter enemies? And perhaps most of all, do the bones and withered flesh encased beneath the sod have any relation at all to the person who once was, or is it merely a remembrance for the ones left behind?

You may think such thoughts, but not for too long. The living need to live. The dead are just one more reminder that we are all headed for the same place. Life is short, joy is fleeting, and time is not to be wasted.

Do you have a dissenting opinion or any opinion at all on the subject? Contact me at george@georgeleecunningham.com and let me know. Meanwhile, you can always subscribe and get an email reminder of blog postings. Your name will not be shared and you may cancel at any time.

A place to share some words of beauty, inspiration, and life. The lyrics this week are all about loss and death. Two of our three selections are country music, because nobody sings about loss and death better than country folks. The first one is about a feeling we have all had when we think of loved ones we have lost. What we wouldn’t give for one more day with that person, just to tell them how much we love and miss them. The second has a gospel sound that recalls a troubled life and the pain felt by those left behind. The third selection is an import from across the ocean, which is so hauntingly beautiful that that it could make a stone weep. Click on the name of the piece to get a video or more information.

One more day, one more time

One more sunset, maybe I’d be satisfied

But then again, I know what it would do

Leave me wishing still for one more day with you

– One More Day Group: Diamond Rio; Writers: Bobby Tomberlin & Steven Dale Jones

I know your life

On earth was troubled

And only you could know the pain.

You weren’t afraid to face the devil,

You were no stranger to the rain.

– Go Rest High on That Mountain Singer and Songwriter: Vince Gill

But when ye come, and all the flowers are dying,

If I am dead, as dead I well may be,

You’ll come and find the place where I am lying,

And kneel and say an Ave there for me.

And I shall hear, though soft you tread above me,

And all my grave will warmer, sweeter be,

For you will bend and tell me that you love me,

And I shall sleep in peace until you come to me

– Danny Boy Singers: Celtic Women; Songwriter: Frederick E. Weatherly

I received a lot of feedback about my remembrance of pal, Larry “Lash” LaRue, getting robbed as a young man working at Taco Bell, but none funnier than the following from Jim Fogarty, who worked with Lash at the Omaha World-Herald, back in the early ’70s.

Fogarty writes:

As far as I’m concerned every day with him was just like the Taco Bell robbery.

I recall once when he walked back from the police station (where I remained) to the newspaper office. He sat down at the re-write desk and immediately pitched face-first into the typewriter keys. Two things had happened. First, he got stung by a bee and didn’t know it. Second, he was allergic to bee stings and didn’t know that, either. He was back in the office by four p.m. writing the story of his bee-sting near miss.

Lash also was a rebel … When he was given crappy assignments he would make masterpieces out of them – and then complain about how crappy they were.

One day the desk got a call about children on their bicycles being attacked by a bird on 92nd Street in Omaha. He drove out, watched what happened each time a kid passed under a certain tree (instant attack and pecks on the head).

Then Lash borrowed a bike and put himself in harm’s way, again. And the newspaper photographer got a perfect photo of the bird – frozen-in-time – as it took its first peck on Lash’s dome. LaRue took the photo to experts who immediately pronounced the attacker to be a “King Bird,” known to be overly protective of nests occupied by baby King Birds. Front page, that was.

Then one Saturday they sent Lash to cover the circus parade – from the train to the downtown auditorium. As any good journalist would do, Lash covered a six-year-old boy watching the parade instead of the parade itself. But to demonstrate his disdain for the assignment, he wrote this lead: ‘A six-year-old boy will love a circus parade as surely as a mongoose will suck a duck egg.’

He turned it in to fellow-rebel Al Pagel who was manning the city desk that day and who let the lead go through, all the way to the next edition. Senior editors were so horrified that they said nothing – to Pagel or LaRue.

###

Lash wasn’t the only legend at the Omaha World Herald. In a May 9, 2013 column for the Tacoma News-Tribune, Lash wrote about his pal Fogarty getting back at a radio reporter who would steal his copy, put it on the air as his own, and basically scoop Fogarty on his own story. You can read that story HERE.

Jim Fogarty, still lives in Omaha, Nebraska, where he is a co-owner of Legacy Preservation, a company that publishes limited-edition personal biographies. You can phone him at (402) 305-7180, email him at Jim@legacypreservation.com or find out more about Legacy Preservation at www.legacypreservation.com

It turns out that my pal, Larry “Lash” LaRue, who died last November, was ahead of his time. I already knew that, but a recent article I read reminded me that Mr. LaRue knew way back when, what social scientists are just figuring out now.

In the 1960s, when Larry was working his way through Long Beach State, he had a gig as the overnight guy at Taco Bell in Long Beach. On the wall behind him was a clock imbedded inside a giant Mexican sunburst.

Late one night, this young kid comes up with a gun, sticks it through the window, and demands all the money. Instead of giving him the cash, Larry whispers to the kid to put the gun down out of sight. “There’s a camera hidden in the clock,” Larry tells him, “just act normal.” The kid looks scared, then says, “OK” and puts the gun down.

Then Larry in a loud voice says, “Yes Sir, two bean burritos and a taco,” speaking for the benefit of the make-believe camera.

He puts the order in the bag, gives it to the would-be robber, then tells the kid to take off before they both get caught. The kid runs off with his bag of fast food, and Larry calls the police.

It turns out that Larry’s dad, Al LaRue, was a lieutenant on the Long Beach Police Department at the time. His dad was irate. How stupid are you, he wanted to know. You risk your life for a couple of hundred bucks that doesn’t even belong to you? Are you insane?

But Larry wasn’t insane. He just didn’t want to get the kid in trouble over a couple of hundred bucks in the Taco Bell register.

The Taco Bell robbery story all happened before I knew Larry, but he told about that night on several occasions when we were out drinking, and I laughed every time. Because it was funny and because that’s the kind of guy Larry was.

Now, 50 years later I read a story on Zocalo by sociology professor Anne Nassauer. The professor writes that social scientists are using closed circuit TV recordings of robberies and other events to discover what makes people act the way they do. Setting up social experiments with human subjects in a lab or doing a survey is always limited by the awareness of the subjects that they are part of a test. And because they are aware, they consciously or unconsciously act as the think they should act.

But on closed-circuit TV, you get a picture of the subjects who are part of a real-life experience rather than a closely controlled experiment. And with the ubiquitous presence of surveillance cameras, there is lots of material to choose from with a wide range of cultures and nationalities. It turns out that most of us follow scripts during encounters with other folks.

“How are you,” somebody says to you.

“I’m good,” you say, even though you may have a toothache and your wife just filed for divorce. “And how about you?”

“I’m doing just fine,” the other person says. “Have a great day.”

“You too,” you answer.

It’s a script, and with some variation, most of us follow it dozens of times a day. It turns out to be the same thing with robberies.

The robber brandishes a gun, bursts into the store, and shouts in an angry voice, “Give me all the money!”

And the clerk? He or she puts their hands up, and turns over the cash.

It’s all part of a script. But it turns out, that’s not the way it always goes. In about a third of robberies, the victim does not follow the script. And when he or she goes off script, it throws the entire robbery dynamic out of sync – kind of like when an actor unexpectedly starts to ad lib in a play.

Sometimes, the clerk doesn’t put up his hands. Sometimes the clerk reaches under the counter, pulls out his or her own gun, and shoots back. Sometimes the clerk is fed up with people just marching in and demanding money and tells the robber to get lost.

Here’s the Zocalo account of a robbery caught on video in Riverbank, California.

‘Two robbers enter the Circle T Market in Riverbank. One carries a large assault rifle, an AK-47. Upon seeing them, the clerk behind the counter puts his hands up. Yet the elderly store owner finds the weapon absurdly big and casually walks up to the robbers, laughing. His shoulders are relaxed and he points the palms of his hands up as if asking them whether they are serious. Both perpetrators are startled upon seeing the elderly man laughing at them. One runs away, while the one with the AK-47 freezes, is tackled, and is later arrested by police. They had robbed numerous stores before.”

Which brings us back to the robbery at Taco Bell so many years ago. It doesn’t always work out as well as one might hope. The young robber could have shot my friend Larry LaRue and killed him before Larry and I ever met. That could have happened, but it didn’t.

It could be that the young robber took the lesson to heart, gave up his plan to be a criminal, and lived a happy and productive life. We would all like to believe that, but it is almost certainly not what really happened. And that’s OK.

Larry did his best for the kid, because that’s the kind of guy Larry was. And maybe in the end that is all that really counts.

Do you have a dissenting opinion or any opinion at all on the subject? Contact me at george@georgeleecunningham.com and let me know. Meanwhile, you can always subscribe and get an email reminder of blog postings. Your name will not be shared and you may cancel at any time.

A place to share some sounds of beauty, inspiration, and life. Sometimes when words are not enough and we feel like a little calm and order in our life we listen to music without words. The nice thing about instrumentals is that you can supply your own feelings to the music. All three of our selections have lyrics to go with them, but sometimes for us, words merely detract from the music. Today we give you both versions, with and without music, so you can make your own decision. The first song, Chandelier by the Brooklyn Duo is an instrumental. The second version, with vocals, is by singer and writer Sia. The second song, Clocks is done as an instrumental by the Dallas String Quartet and with lyrics by Coldplay. The third song – Beethoven’s 5 Secrets – is a combination of Beethoven and the OneRepublic song Secret. Again we have it with lyrics and without. Click on the name of the piece to get a video or more information.

– Chandelier as instrumental Artist: Brooklyn Duo; Writers: Jesse Shatkin & Sia Furler

I’m gonna swing from the chandelier, from the chandelier

I’m gonna live like tomorrow doesn’t exist

Like it doesn’t exist

I’m gonna fly like a bird through the night, feel my tears as they dry

I’m gonna swing from the chandelier, from the chandelier

– Chandelier with lyrics Artist: Sia

###

– Clocks as instrumental Artists: Dallas String Quartet; Writers: Guy Rupert Berryman, Jonathan Mark Buckland, William Champion, and Christopher Anthony John Martin

Confusion that never stops

The closing walls and the ticking clocks gonna

Come back and take you home

I could not stop, that you now know, singing

Come out upon my seas

Cursed missed opportunities am I

A part of the cure

Or am I part of the disease, singing

– Clocks with lyrics Group: Coldplay

###

– Beethoven’s 5 Secrets Artists: The Piano Guys – OneRepublic Writer: Ludwig von Beethoven, Ryan Tedder

Tell me what you want to hear

Something that will light those ears

Sick of all the insincere

I’m gonna give all my secrets away

This time, don’t need another perfect lie

Don’t care if critics ever jump in line

I’m gonna give all my secrets away

– Beethoven’s 5 Secrets with Lyrics Artists: The Piano Guys – OneRepublic with Singers Tiffany Alvord; Writer Ryan Tedder

– Secrets Group: OneRepublic, Writer and singer: Ryan Tedder